|

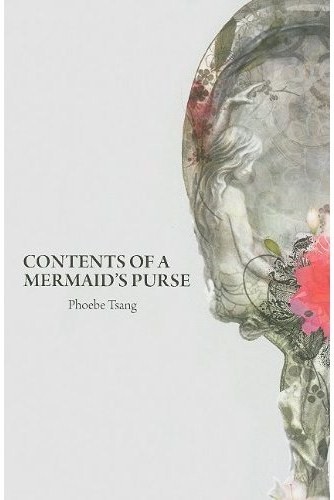

Contents of a Mermaid’s Purse

Tightrope Books Paperback, 62 pages ISBN 1-932195-01-7 Link to Purchase Reviewed by Ann E. Michael |

|

It’s in the news all the time now, a catch-phrase: “global.” Recently the president of the college where I work told the humanities department faculty that he would like to see more globalization in the upper-level lit-studies classes. I’m not sure he really knows what he means by “global literature,” but the work of Phoebe Tsang might fit the bill in the best possible way. Her collection Contents of a Mermaid’s Purse references Cinderella, Rapunzel, the Emerald City, Hong Kong, the River Fulda, New York, Banff National Park, the Aegean, De Chirico, drunkenness, dreams, and Rumi. Besides, she was born in Hong Kong, raised in England, and lives in Canada. But I am getting ahead of myself; and I would hate to leverage Tsang’s collection into a too-easy category, even one as broad as “global literature.”

Few poets aim to be considered “global.” They are generally endeavoring for universality instead, the tone or rhythm or metaphor that stays with the reader, any reader—that’s why so many poems talk about love. Among Tsang’s themes in this book is love’s transitional strangeness, a love for places and stories, for images culled from fairytales, art, and music. Romantic love, as Tsang describes it, is a thing that “changes once/you come down/from the mountain.” There are poems here that evoke youthful romance: early “indiscretion” of which the “luxury [is] being cheap/but not thrifty,” and headlong love “disguised by the curse of your desire,” and lost love and mother love and love of the arts.

Then there is the risk any writer takes when drawing inspiration, imagery or metaphor from fairytale texts—the risk of cliché. Phoebe Tsang’s re-imaginings of folk and fairy tales generally work because in most of these poems her fluid, simple language does not become stilted or over-familiar. The most memorable poems in this collection, however, are not the revisited fairytales (with the exception of the enchanting prose poem “The Fox and the Lady”) but the pieces that allude to such inspirations without making them foremost in the reader’s mind.

An example from section I of “Unfinished Knitting Project”:

because the sky today is half black

and half blue like the princess

who fell asleep on top of a peabecause I woke this afternoon

to the scratching of squirrels behind

the bathroom tiles, digging

for comfort in damp places

After the opening stanza with its Andersen allusion, Tsang gives us “real” place (the house with the squirrel problem) containing drawers full of real sweaters that, in the fourth stanza, begin to sneak out and to “shake loose stitches like worsted/strands of Rapunzel’s tresses.” In the next section, the poem’s speaker watches spiders on the ceiling, listens to construction workers hammering. The poem is not a fairytale retold and needs not clarify the answer of “where”; the princess merely felt something and awakened, like the narrator. Now, the speaker finds herself in an ambiguous waiting zone—the place between awake and asleep, dream and reality, where everything is unfinished and where we are not assured of a happy ending. Famous princesses become allusions, not origins. The approach works.

Often in these poems, the hearer of fairytales before bedtime finds herself crossing the borders of dreams which seep into the realities of love affairs, hotels and highways, “white-painted way stations blistering and peeling.” Here is where the global aspect of Tsang’s writing lifts the work to more intriguing elevations, such as perspectives from the skyscrapers of Hong Kong in “Emerald City Blues” or views of the crow-like “hunchbacked bulk of the cathedral” in a German city. The speaker traveling from waking to sleeping is also the speaker who travels the globe, and Tsang’s poems are often stylistic crossings as well: “Kiss” with its epigraph and stanzaic structure evoking Rumi; “Dream after a Painting by De Chirico” and “Recurring Highway Incident”—among others—confirming surrealism’s place in contemporary poems; “Cemetery on Tsz Wan Shan” and “The Idea of Home” drawing on the mood and imagery of Chinese poetry; the dreamily-appropriate employment of loose couplets in “Cabin Fever with the Tree Pirate” and the fascinating repeated sounds that animate “Blood Roses”:

But remember, the body was built as a lair; who knows

what has come in with the rain, the roses and the roots

of roses, with their thorns and rosaries? I roseas if suddenly awakened…

Phoebe Tsang demonstrates that poets can continue to accomplish interesting and beautiful things through the use of familiar tales and the dream/reality borderline, that the possibilities for such material do not stop at Sexton (or Bettelheim, for that matter). Reverse the idea that the speaker is the poet in “Golden Goose Pie” and Tsang becomes the “you” in these lines:

I thought fairytales were fated

to sleep eternally, hushed

as the forgotten voice of the mother,but you were already halfway up

the beanstalk, one hand held out

for mine—Let’s go!

With the publication of Contents of a Mermaid’s Purse, Phoebe Tsang grabs the reader’s hand to show how classic motifs can dwell in globalized, 21st-century literature.