|

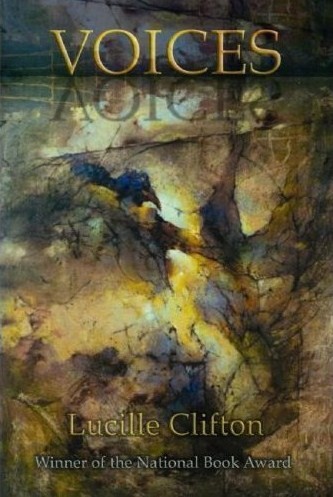

Voices

BOA Editions Soft cover, 64 pages ISBN 978-1-934414-12-5 Link to Purchase Reviewed by Mary Jane Lupton |

|

The celebrated African American poet Lucille Clifton died at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore on February 13, 2010. When I had last talked to Clifton during a telephone interview in October of 2005, she mentioned that she was working on a volume of poetry tentatively titled Colored Women. Among her subjects were Sally Hemings, Aunt Jemima, and Pocahontas, whose Indian name was Mataoka.

A few of these women from the past do appear in Clifton’s final volume, titled not Colored Women but Voices. As in all of her poetry, characters from history and popular culture are transformed in Voices by Clifton’s personal, uncapitalized “i.”

My favorite among them is “cream of wheat,” a poem about the infamous, boxed breakfast food advertised by a black servant named “Rastus.” We learn that at night Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus wander freely through the aisles of grocery stores–homeless, nameless, identified only by their kerchiefs, their chef’s hats, and their happy black faces.

Rastus

i read in an old paper

i was called rastus

but no mother ever

gave that to her son….

“cream of wheat” is a poem in “hearing,” the first section of Voices.

In “hearing” Clifton presents several animal poems, including “raccoon prayer,” “horse prayer,” and “dog’s god.” These poems are reminiscent of her magical fox sequence, published in The Terrible Stories in 1996. They also resemble the animal poems of contemporary Native American poets James Welch, Leslie Silko, and Joy Harjo. Like traditional and modern Indian poets, Clifton often chants in cycles as she prays for the wounded earth and its threatened inhabitants.

In her 1987 volume Next, the warrior Crazy Horse (Tashunka Witco) is featured in a sequence of four poems. In Voices she again revives his spirit, concluding her tribute to the famous Sioux with the familiar chant, “it is a good day / to die.” “hearing” is rich with Indian names like “Father of What Runs and Swims,” “mataoka,” and “witko: aka crazy horse.” The section ends with the mournful autobiographical poem “sorrows,” which is reproduced on the back cover.

In section two, “being heard,” one finds images that have become familiar to readers of Clifton’s poetry. There are two poems about her father’s abuse of her mother, expressed in the language of the kitchen:

this is what I know

some womens days

are spooned out

in the kitchen of their lives

In one untitled poem she alludes to her father’s “probing fingers,” but she is not nearly as specific about Samuel Sayles’ sexual violations as she had been in Next and in her 2004 book, Mercy, where she claims that she is grateful that her father did not “replace his fingers with his thing.”

The third section of Voices, “ten oxherding pictures,” is more strenuous than the earlier two. It is a series of philosophical meditations that recalls the spiritual quest of Guatama Buddha, a theme which Clifton had explored in “california lessons” (Next, 1987).

She tells us in a note following the sequence that “ten oxherding pictures” is based on an “allegorical series composed as a training guide for Chinese Buddhist monks.” She had never seen the pictures but only their titles before she wrote the ten poems; but, if one is to rely on the internet, she had evidently published an earlier version of the oxherding poems in the Winter1999 issue of Callaloo (volume 22, number 1).

Some background seems necessary in preparing the reader for the complexity of Clifton’s series. Wikipedia relates the ten stages of the “Ox Herding Pictures” to the ten stages of the progress towards enlightenment and wisdom in Zen Buddhism. As is her custom, Clifton personalizes the philosophical abstractions. Like the monks many centuries before her, she must struggle to catch and tame the bull or ox.

“6th picture

coming back on the ox’s back”i mount the ox

and we shamble

on toward the city together“7th picture

the ox forgotten leaving the man

alone”i have been arriving

fifty years parents

children lovers

have walked with me

eating me like cake

and I am a good baker….

In “ten oxherding pictures” hands are a dominant motif. Lucille Clifton was born with six fingers on each hand, as was her mother. At the beginning of the series, when the journey begins, the Zen poet believes that her hands belong to the ox. When the ox, the symbol of enlightenment, summons her in the second poem, it is through these hands. Hands appear in all but two of the “pictures” (the 3rd and the 8th). In the tenth “picture,” the monk who is Lucille arrives at the gates of the city, and “the hands begin to move.”

The series ends in a three-line thought entitled “end of meditation’:

what is ox

ox is

what

To read Lucille Clifton is to apply all of one’s concentration and yet to be looking for her autobiographical data and even her humor, as in the pun on “buffalo,” the city where she grew up but also an American ox (“second picture / seeing the traces.”)

Other themes in the third section illuminate the voices Clifton hears, voices who summon her on her journey to wisdom as her dead mother’s voice had called to her in the poem “the death of thelma sayles” (Next 51). In Zen tradition, Clifton hears voices who echo the sound of silence. These themes of voices, wisdom, the hands, the ox, and silence help to enlighten the title of this short but brilliant collection and to fuse its separate parts.

With Clifton’s death in February of 2010, her voice is physically silenced. But the spirit of Lucille, whose name means light, shall shine indefinitely, for she was a “good baker” of poems.