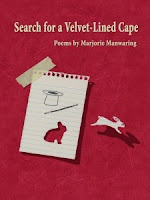

Search for a Velvet-Lined Cape

Marjorie Manwaring

Mayapple Press, 2013

Paperback, 86 pp

ISBN 978-1-936419-15-9

Purchase Link

Reviewed by PQ Contributing Editor Ann E. Michael

Inquisitive creatures that we are, we find the unexplained and the mysterious compelling; the idea of magic is surely a human invention, yet we want to believe in it, to find proof that it exists. All too often, we are tempted into gullibility by what appears to be paranormal but which turns out to be sleight of hand. It is the tension between desiring magic to be “real” and the skepticism that makes us aware charlatans will take advantage of our desires that Marjorie Manwaring addresses in her book Search for a Velvet-Lined Cape. Under this tension lies the problem of trust and trustworthiness, which she also subtly explores in these poems.

The collection offers what readers might expect in terms of tropes, given the theme: rabbits and silk hats, hocus-pocus, mentalists, shell games, and levitation. Manwaring divides her collection into five parts, each one an allusion to stage magic and each section picks up the themes of dream-states, wishes, disillusionment and desires in different ways. For example, the third section, Open Sesame, begins with “The Magician’s Mother,” a prose poem suggesting innate talent and the thwarting of parental expectations, and moves through memoir-type pieces that connect with childhood and adolescence, when we are especially susceptible to magic’s allure or particularly eager to become escape artists. Another notable prose poem in the Open Sesame “chapter”—there are 15 prose poems in the book—titled “Charm,” begins with desire (a child eyeing a row of supermarket gumball machines) and leads to what the child “needs,” unknown to her at first: a tiny magnifying glass, “something small that lets you see things even smaller.” Examination feels necessary here, as the speakers in these poems must watch closely to tell whether the magicians are fooling the eye and heart or are genuine enough to be trusted.

The section titled Now You See It… offers a series of vanishings, escapes, and other releases, from doves to lovers to snowmen. The mood’s one of endangerment in poems like “Yellow,” with its predatory wasps that refuse to leave the house to “scavenge the abundance outside, ripe plums / fallen beneath the tree, orange meat busting / out of purple skins.” Other predators include commercial franchises, superhighways, mental illness. There exists a dark side to magic; Manwaring includes it here, mentioning not only the questionable feats of the Amazing Kreskin but also the kind of magic encountered in fairy tales, where the powers are indeed powers, often ambivalent and available only to those characters who are honest, innocent, or foolish.

Manwaring employs several approaches to poems in terms of form, but she seems most at home with the prose poem. The blocky shape of prose poems serves well to make these pieces operate like stage sets or magicians’ boxes which, on examination, turn out to be deeper than they appear. Hidden drawers? Secret passages? False bottoms? All very likely in the case of poems that use illusion as metaphor: “…in that cobwebbed corner, the marriage certificate, the gold band, the thin flask of shame,” she writes in “Reappearing.” The magic seems possible to most of her characters and speakers, in fact. The final poem, “Company Party,” finds the speaker defending an adolescent “levitation” party game that was

played late at night in candle-lit basements

or bedrooms by girls in pajamas ready to be amazed

and spooked. He was saying it merely proves

the power of suggestion and the constancy

of physics, but I wasn’t buying and said so…

The skeptical naysayer continues his rational argument while the CEO and middle managers float toward the disco ball overhead. With this as the concluding poem in the collection, Manwaring places herself among those who believe in magic, on some level, while remaining quite aware of the possibility that she risks being either taken advantage of or becoming disillusioned. She also manages to end the book with her sly humor, which serves her so well in many of these poems. “Rejection Letter from Gertrude Stein,” for example, begins “Dear Poet Dear Author Dear Someone:” and, in short lines, synthesizes standard rejection-slip language with Steinian syntax and wordplay, to excellent and hilarious effect.

Marjorie Manwaring has taken on a challenge with this material because readers are likely to find magic overly familiar—fairy tales, sideshows, celebrity stage magicians and shell-game or card-game street tricksters are thematically easy. When a poet employs stage magic as imagery, the reader naturally expects the unexpected, so the surprise of the poem has to be especially fresh. Manwaring has managed, however, to infuse her work with dashes of the unexpected through her use of humor, pop culture references, a variety of forms, and shifts in perspective that keep the more traditional metaphors from cliché.

Ann E. Michael is a poet, essayist, and educator whose most recent poetry collection is Water-Rites (2012). She lives in eastern PA where she is Writing Coordinator at DeSales University. Her website: www.annemichael.com.