Interview with Stanley Plumly

by Georgia Jones-Davis

|

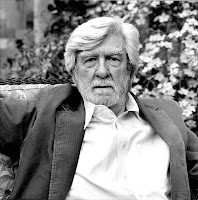

| Stanley Plumly. Credit: Emma Norman |

Stanley Plumly, the Poet Laureate of Maryland, is a Distinguished University Professor at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of several collections of poetry including Boy on the Step,The Marriage in the Trees and Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me.

More recently with W.W. Norton he has published Old Heart, Orphan Hours, and Posthumous Keats, a biographical meditation. Plumly has won numerous awards including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, the John William Corrington Award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature (2010), Beal Award in Biography from PEN (2009), and both the Paterson Poetry Prize and Los Angeles Times Book Award for his collection, Old Heart in 2008.

He is a founding faculty member of the Gettysburg Review Writers Conference, which I where I met him and he was delighted to be interviewed for Poets’ Quarterly.

You grew up in a semi-rural world in Eastern Ohio that sounds fascinating, even other-worldly, but not an environment that necessarily offered poetry as a party of the daily routine.

Like almost everyone, I first encountered serious poetry in high school (in the 1950s) — from Kipling to Cummings. My teacher was Nellie Otte, who took an Interest in a kind of prose-poetry I was writing. Autobiographical paragraphs, Really. Otherwise, I haunted the school and public libraries. Our local library was called the Flesh Public Library –never forgotten it.

I grew up in both eastern and western Ohio, Pennsylvania on one side, Indiana on the other. I was born in a little Quaker town in up-country Belmont, a farming region, where horses were used to plow since the terrain was so hilly. James Wright was born in the same county, as was William Dean Howells. We all had to leave it to write.

How are you led to the writing of a poem? In other words, how does a poem out there in the ether reach out to you?

I have no idea what an idea is — it’s such an abstraction. So poems for me tend to start from memory, a source of associations. Narrative, therefore, as a flexible instrument is important to me. And the natural world, present and past.

Orphan Hours, your latest collection of poems, is a beautiful, wise and haunting book that could only have been written at the “edge” of time, as it were. Near the border or edge of the field that is a long lived life, a book that could only grow out of many experiences, long spells of writing, loving, travel, thought.

How has the practice of poetry changed for you as you have changed and grown older? Has poetry itself, aged in a sense and how?

Orphan Hours must speak for itself. Thanks for the nice words. It’s a book looking at the horizon, just as the sun is disappearing in the trees and through the windows. The vesper hour.

Do you have a sacred writing ritual–a time of day or night that you love to work, a place with a great window?

I work in the morning, early — everything else (cooking, drinking, reading, Thinking, talking, shopping) is for the leftover hours.

Who are the writers and poets you return to again and again?

I love a few of my contemporaries, whom I shall not name.But, I tend to read against my taste– it’s healthy and lively. Otherwise, I go back to the verities, the great poems that have made us possible, starting with Bishop and going backwards.

Along with Aileen Ward, Walter Jackson Bate, Robert Gittings, Andrew Motion etc. you have the mysterious and ever vanishing John Keats into focus for us. I can think of no other poet from the past who commands such awe and love as Keats.

Could you tell us a little about your remarkable relationship with Keats — and a relationship it is, a sort of friendship I am convinced, not only academic scholarship.

Ward’s biography of Keats is the best straight-forward narrative. Bate’s is far by the best critical biography. Gittings is good on influences and outré opinion. The newer biographies are compendiums of these three, plus the marvelous Amy Lowell auto and bio of Keats (It is about her as well as Keats.).

My own sense of Keats is taken, first, from The Letters, which are the finest,most interesting, most vital, most aesthetically astute ever written. Then The Odes.Then the rest of the poetry.Then the biographies and just about everything else written about Keats. Then the travel, to every place he ever was. More than once.I’ve lived in London half-a-dozen times. Twenty, twenty-five years of more or less involvement.

What are your thoughts on poetry as practiced in the English language today?In what ways have MFA programs influenced American poetry?

Poetry today is brilliant, exciting, confusing, in excess of the talent it takes to write it, and diverse in the extreme. The art of poetry is to be separated from the careerism that too often gets in the way of good writing. Time tends to sort things out–the good from the bad, the bad from the ugly.

MFA programs–if they are any good — are “singing schools.” Vocational entities, I think not.

Georgia Jones-Davis has published poetry in Westwind, The Bicycle Review, Brevities, South Bank Poetry, LondonandEclipse. In 2010, she was honored as one of the Newer Poets by Beyond Baroque and the Los Angeles Public Library. She is the author of Blue Poodle, a chapbook by Finishing Line Press.