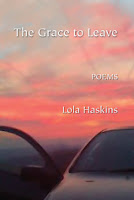

The Grace to Leave

Lola Haskins

Anhinga Press, 2012

Perfect bound, 68 pages

ISBN: 978-1-934695-28-9

Purchase Link

Reviewed by PQ Contributing Editor Arthur McMaster

Florida poet and educator Lola Haskins asks in her poem “Moor,” this not-so-rhetorical question, “and what survives? Only the voracious” she offers, then adds what more she sees:

gorse with its dark green prickles,

its seeds that pop like a greedy baby’s lips:

bracken whose spores in fall cause cancer;

heather, tough, clumping in gangs…

and each of these tries to choke the rest.

The central Florida landscape and several of its arcane creatures populate her poems in the first part of the book—the osprey, the wood storks “hunched like priests in the trees.” She includes as well the “occasional alligator, its blunt nose / and hooded eyes half submerged. ” She has trained her eye and powers of observation to what is seldom noticed. Later, the properties of our own bodies are revelatory, not least the great toe, “a house with one window.”

The reader will find Haskins asking questions of the attentive reader, cajoling us to consider more carefully what we might take for granted. In “Anguish as a Second Language” we are asked:

Of what is your hometown made? Wood? Concrete? Mud?

How easily do its buildings burn or push over? How do you know?

Have we been inattentive? I can’t help but think of the town of Rosewood, Florida, not far from Ms. Haskins’ hometown of Gainesville. A town burned to the ground in January of 1923 following a race riot. A town made of wood and perhaps a little concrete and mud; a town largely forgotten. And maybe we are, all of us, inattentive.

Soon the poet instructs: “Tell us about an uncle you loved as a child. Where is he now?” Donald Justice, who taught for several years at the University of Florida, as does Lola Haskins, did the theme of family and personal loss as well or better than any of his peers. His is a fine model. The essence of Haskins’ poems is the wealth of small and smaller things surrounding us that make a life. Her poems flow from an understanding and just how easily we come to take them all for granted.

In a three-part prose poem titled “Some Geometries of Love,” the poet offers an explanation for why we seem to take only so much of the word to ourselves, tempted perhaps to let the rest of it simply go. I offer here in full the second part of her outstanding triptych. This section of the poem is titled “Circle.” It tells us something vital about whom and what we have chosen to be, to know:

How many ways can six pigs look at each other if each pig looks at one

other pig and each pig is looked at by at least one pig? It is problems

like this that cause so many poets to abandon paper and pencil after

high school. It’s not that they can’t compute. It’s that the possibilities

frighten them. And also because they understand that even if they

did derive the very answer listed upside down on page 69, it would be

beside the point since in philosophy every proposition is, in the end,

unknowable. For instance: although Jason may look at Margaret and

be seen by Joe, and John may look at Jenny and be seen by Sue, what

happens if Joe has only one leg or John is Deaf? And what is the effect

of Erin’s Catholicism? To answer such questions, there are not enough

pencils in the world.

There are not enough pencils. Not enough good poems and questions, such as these.

Arthur McMaster‘s poems have appeared in such journals as North American Review, Poetry East, Southwest Review, Rhino, and Subtropics, with one Pushcart nomination. He has two published chapbooks, the first having been selected by the South Carolina Arts Commission’s Poetry Initiative. Arthur teaches creative writing (poetry and fiction) and American literature, at Converse College, in Spartanburg.