|

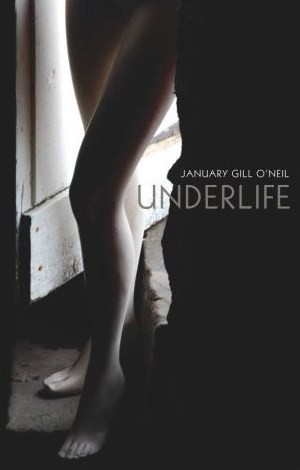

Underlife

Cavan Kerry Press Perfect bound, 69 pages ISBN 978-1-933880-16-7 Link to Purchase Reviewed by Claire Keyes |

|

“Protect your strange and beautiful underlife,” January Gill O’Neill urges at the end of her first book of poems. She should know, if the poems of Underlife are any measure. The arc of the volume takes readers from childhood to adulthood to motherhood, from protecting her children to protecting her own hard-won sovereignty over her own soul. What makes this first book compelling is the gradual deepening of the content and the growing skill of the poet. Sassy at times, O’Neill can also sound wise and knowing. Her race is at times her subject, but more often simply an integral part of her identity, a given. These are the poems of a woman who becomes a self in the world, growing more confident as that self evolves.

The best poems in the book delight us with their freshness of language, the subtle urgency of their tone and the wise knowingness that pervades the lines. Take “How to Make a Crab Cake,” for example. What begins as a recipe poem turns into a lesson on how to live your life:

Always, it’s a matter of guesswork

but you hold it together

by the simplest of ingredientsfor this is how the body learns to be generous,

to forgive the flaws inherited

and enjoy what lies ahead.

O’Neill follows this poem with “In Praise of Okra” and we know we are in the presence of someone from the southern United States, an ardent lover of this vegetable’s “stringy, slippery texture.” Addressing the okra, she introduces its origins: “You were brought from Africa/ as seeds, hidden in the ears and hair of slaves.” Her love for okra is more than historical; it goes deep into family customs:

Nothing was wasted in our kitchens.

We took the unused and the throwaways

and made feasts; we taught our children

how to survive,

adapt.

Had the poem stopped there, she would have made her point, but O’Neill’s aesthetics is not about making points. She concludes her poem with a visceral image, with felt knowledge:

Your fibrous skin

melts in my mouth-

green flecks of flavor,

still tough, unbruised,

part of the fabric of earth.

Soul food.

Does she get away with that last, over-used phrase? Perhaps.

As the poems of Underlife progress from childhood memories to young adulthood to married life they deepen thematically and stylistically. “The Small Plans” concerns a life-threatening illness and an infant who “won’t remember” any of it. The poem serves as a reminder of the parents’ horror and dread. At the same time, the poet urges her child to:

Forget the tubes, the IVs.

the doctors with their bad jokes,

the nurses with their latexed hands.But,Not your father feeding you sugar water

with a cotton swab, or your mother

kissing your lips pursed tight as a clasp,

those perfect lips God gave you.

Building her poem through a series of lists, O’Neill captures a vivid hospital scene. Once God enters the poem, the tone shifts to philosophical considerations: “Is it true He doesn’t give you more than you can bear?” This question allows the poem to move to its climax:

Forget I asked.

Forget Him.

Forget the small plans we have for today,

watching you vanish and reappear

in the space of my hands

When motherhood doesn’t press so heavily upon the poet, she composes poems that are sheer fun like “What Mommy Wants.” In this self-assured and sexy poem, a pair of shoes, Candies to be exact, play the important role of embodying the underlife of the speaker. As she imagines wearing the “high-heeled wooden stilettos,” she re-embraces her own sexuality, becomes “a tawdry wench,” her legs “curvy and dangerous.”

Just as those “Candies” signify a departure from the wholesome “Mommy” role, a companion poem, “Discipline,” gives us a perverse speaker who delights in corporal punishment. The underlife in this poem emerges in violent imagery:

Hit it with last Sunday’s sports section

Rolled up like a nightstick.

Or a Louisville slugger

Hit it with the back of your hand

Hit it with the flat of your palm

Pop it in the mouth

On the head

On the ears so they ring

Is the “it” an unruly pet, an overactive child? To tame it, the speaker advocates: “Hit it again and again and again.” The speaker’s mask slips a bit in the ending of the poem and we see the love/hate relationship with the recalcitrant other:

Hit it because you feed it

You keep it warm

You give it a place to sleep

And still it won’t listen

Hit it because it loves you no matter what

Hit it because you can.

The underlife emerges in this poem as negative and destructive, not particularly “strange and beautiful.” Even so, “Discipline” says something about O’Neill’s willingness to know and understand all the facets that make up the human psyche.

In the end, we come away from reading Underlife with respect for the deepening complexity of the poet who rescued the child she was from her parents, then rescued the adult woman from an enveloping suburbia: house, kids, husband. We come away also with favorite lines echoing: “Days press down on me/ like an iron on a silk blouse.” Lightning bugs that “frolic and sparkle above the delicious scent of honeysuckle.” “I am a plum black garnish to the day.” O’Neill’s poems do more than “garnish the day”; they bring the everyday-from vegetables to shoes and everything in-between-to throbbing life.