|

The Ravenous Audience

Akashic Books (Black Goat) Perfect bound, 144 pages ISBN: 978-1-933354-88-0 Link to Purchase Reviewed by Carolee Sherwood |

|

It’s tempting for me to talk about Kate Durbin’s debut collection in terms of its politics, and it’s tempting to use intense language to describe its aesthetic. But the blurbs on the back of the book (adjectives like “brutal,” “deeply feminist” and “grotesque” and promises of “horrors,” “intellect” and “reanimation”) do both of those jobs famously.

And although the word “gurlesque” does not appear on the jacket of The Ravenous Audience, it could fit easily next to “avant-garde” or “feminist revisionist.” Despite an infinite personal interest in (and admiration for) poems with that jagged edge, I am going to take off the table all talk of the “girlie” and the “grotesque” (components of the gurlesque as outlined by Arielle Greenberg). Yes, this collection is bold and honest about the female body and the female experience. Yes, it retells familiar stories of female icons. Yes, it provokes strong responses.

Yet, even with these powerful tools at hand, what entices me most about The Ravenous Audience is the book as a work of art. The force of the collection is not what Durbin shows us (violation, obsession, blood, feces, cum, menses), but how she shows us.

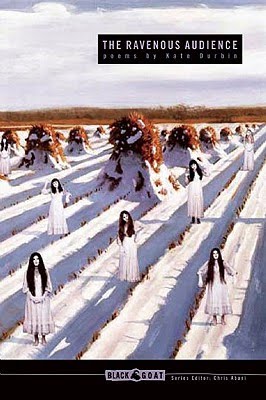

The cover of The Ravenous Audience is this: haunted, stiffly-posed, identically-dressed women (equal parts doll and zombie) standing in an already-harvested and snow-covered field in which shadows are as prominent as anything else. I remark on the artwork not because I can point to the image as the collection’s single metaphor (to do so would be fool-hardy) but because it is a stunning collage, and collage — as an act of gathering, as an act of presentation — encompasses for me the experience of Durbin’s poems.

Collage as something concrete

Collage is both action (verb) and object (noun). The poems in this collection reveal themselves as both process and product, not only through how they appear on the page (product) but also through hints about how they came to be (process).

For example, we learn from the book’s end notes that Durbin often cuts lines of dialog from films and pastes them into her poems. In fact, the poem “36 fillette” is comprised entirely of lines of dialog from a French film by the same name.

As a found poem, “36 fillette” is, literally, a collage, but Durbin uses her own originality to select and stage the pieces. She constructs the poem so that the pace hastens toward a danger we know, even though it isn’t revealed specifically. We hear the comments, pauses and questions of the men (“you little slut” and “how old are you?”) escalate into a frenzy (“how old are you? how old are you? how old are you?” and “from now on you can scream you can struggle because now I know you want to I also want to up there you don’t want to but down here you are drippingwithdesire … “). Durbin achieves this by collapsing the boundaries most usually enforced by the rules of grammar and challenging the way in which words traditionally hold their space on the page.

This is a mirror of the collage process: breaking things apart and putting them back together.

Often, this effect is accomplished visually. Throughout the collection, Durbin uses many typesetting techniques to add a visual element to her poems. She uses italics, all caps, no caps, an abundance of white space, a lack of white space and pictorial symbols (like the butterfly graphic in “Our Marilyn(s): Interview” and the star graphic and font changes in “Mostly Silent Movie: Starring Clara Bow”). She plays with margins and mixes poetry in lines with prose poetry.

These special effects are always in service to the poems. Though “Doll Dress” is only about thirty words, it is a 3-page poem. It is mostly white space, presenting irony with the words “embellish” and “adorn” to which it draws attention. Durbin employs visual impact similarly on a page in the long poem about Amelia Earhart. The page (a full section of the poem) is blank except the lonely heading: “LOSS.”

Another technique Durbin utilizes to enhance meaning via visual impact is to present words that appear to be single words but are actually word combinations. In the quote above from “36 fillette,” for example, there is “drippingwithdesire.” “Doll Disrobed: Notes on the Culinary Nature of the Taking Off of Clothes from the Womanbody” uses this brand of compound word in its title, and its lines incorporate several: “skinfatmusclebone,” “nippleshairscars,” as well as variations on “womanbody” including “herbody” and “femalebody.” The poem “Execrate” uses “womanspeak,” “firstfruitflesh,” “bloodnectar” and “bloodbubble.”

Just as Durbin blends words, she merges differing styles of text within single poems. One trick is to borrow jargon from two distinct areas and flow between them seamlessly, as in “Doll Disrobed” (mentioned above) which uses language about unclothing alongside language about cooking: “Hack denim hot pants./ Tear muscle from muscle.”

Another trick is to flow between texts with different purposes — lists and narratives, for example, as in the poem “A Real Young Girl.” This poem is a numbered list interrupted several times by segments of narration. The narration is full of images — among them a spoon, a cigarette, an egg crushed in a hand, an old bike, a dog, a beach, barbed wire — and they are glued together not by a progression of time or by cause and effect or any other familiar construct. Very simply, they are detained in the space occupied by the list and collectively tell us something about the girl in the poem.

Collage as something abstract

As an artistic medium, collage operates on a level deeper than its visual impact. Collage is a deconstruction of what exists, a manipulation of materials and, finally, the presentation of a new configuration. Using “36 fillette” (described above) as an example, we can see Durbin chopping up the dialog from the film; manipulating order, punctuation and spelling; and constructing a new story, which, in this case, is the anticipated assault upon the “you.” The energy is apparent.

Additional energy in collage comes from the juxtaposition of images and the strangeness of something altered. Durbin’s poems reinforce these sensations, and I found the approach extremely compatible with the difficult topics the poems address. Exploring sexuality, being violated, becoming a woman, getting lost, being stereotyped — all these can be surreal experiences. Memories and ideas of them are odd compositions of the real and unreal, here and not here. They operate in the confused realm between. It is the realm of collage and of The Ravenous Audience.

“Little Red’s Ride,” for example, uses recognizable images from the fairy tale but alters them. Grandma is “too old, too useless.” Little Red Riding Hood doesn’t encounter a wolf, she encounters a “wolfprince.” She is not ambushed by danger; she sees it and goes toward it. She is “clever, with that 60/40 animal sight,/ A half-mile back spotting the paw in the window, beckoning.”

Snippets of the familiar are similarly embellished in the persona poem “Amelia Earhart: Fragments Found in a 1937 Aviator’s Boot.” In addition to the title itself which suggests collage, the poem is comprised of snippets of thought that could have been snatched from Amelia. Her story unfolds unpredictably because of the skill with which Durbin juxtaposes opposites, such as “That pleasure. That fear” and “the pull of earth, that solid home./ Soaring./ At 300 feet, I knew I was meant for indefinite sky.” Throughout the poem, we move back and forth in time. We navigate what is known (“Calling and calling; no response”) and what can’t be known (F “banged his head in the fall, so I bandaged it with my scarf. Now the blood has seeped through and is running into his eyes”).

The brilliance of juxtapositions in The Ravenous Audience isn’t restricted to the confines of individual poems; the architecture of the collection reflects the layers of collage, as well. The very earthy “New Creature” and “Bearlife” are followed jarringly (dramatic effect) by “Prince Polyester.” Several pairs of poems remind us about interplay, as well; there is “An Unremarkable Dream” and its sequel of the same name, “Learning to Read” and “Unlearning to Read,” “Doll Dress” and “Doll Disrobed.”

In addition, there are two Marilyn Monroe poems, and it is the work about Marilyn that illustrates the highest role of collage in the collection: a collaged reality preferable to singular one.

In “Our Marilyn(s): Interview,” Durbin writes in the voice of the icon: “A or B, sugar tell me (what they say) — you Norma Jean today, or are you Marilyn Monroe?// What I want to know is, where’d the rest of the alphabet run off to?” The poem seems to say the tragedy is in believing female icons to be simple, singular objects. In our worship, we disallow complexity. We disregard the layers. Collage, in contrast, shows beauty in the inclusion of many different notions. Collage shows that we can never really capture any one female and her experience. It shows that the process of integrating and disintegrating is ongoing, is happening now as we watch and participate.