|

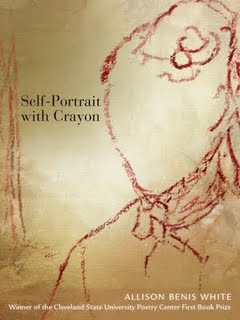

Self-Portrait with Crayon

Cleveland State University Poetry Center Soft-cover, 63 pages ISBN 978-1-880834-83-1 Link to Purchase Reviewed by Emma Bolden |

|

Allison Benis White’s Self-Portrait with Crayon, chosen by Robert Hill Long as the winner of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s 2008 first book prize, contains a linked series of searing prose poems which circle around the idea of looking. White explores the motion and means of the body, and of its representations in various media: dance, poetry, art about dance, poetry about art about dance, and so forth. This is ekphrasis taken to the next level, beyond mere representation of art into questions about the very nature of art and representation itself, about seeing and looking and the lenses through which we choose to see.

White introduces and approaches these ideas regarding representation through a series of poems about Degas and his work. In the first poem, “From Degas’ Sketchbook,” the speaker declares that “this is an external narrative” and moves into an exploration of the fears and desires which drive us to narrate and therefore to represent, no matter the medium: “It is common to know very little, if anything. The point is to stay clam. To be found before you disappear.” In this poem, White sets up the pervasive theme regarding art and its abilities, celebrating both the permanence of art and its ability to capture a moment already fleeing. Art, therefore, has the ability to awaken in the creator and the viewer this simultaneous sense of time as something which passes but which also, once it occurs, will exist forever; a viewer of Degas’ work, for instance, thinks “of broken snow, but this is permanent.” While she celebrates visual art’s ability to create this kind of passing yet permanent impression, White laments the difficulty of capturing such an impression in words. She observes a woman bending to touch her ankle on a bench, and wonders if this is “in order to communicate a small, but consistent pain. The kind that makes you look at pictures because words are not sufficient to describe it.” Such moments are the warp and weft of life itself, and, White implies in “Waiting,” woven this way by divine intent: “When a child throws a stone into a lake, God is pleased, and opens in rings, then fades to prompt the child to throw again.” Beauty exists for a moment only, but can be preserved in art; the question White raises, however, is that of what happens to moments which are not preserved. “When a child floats on a paper boat, she wonders, Where do stones go after they’ve pleased God;” God’s answer speaks of the possibility to capture and therefore to preserve in each of us: “There are hundreds of wet stones in your mouth – and inside stone, the possibility of black unopened umbrellas.”

Creativity, like pregnancy, becomes a process of possibility, linked to the Russian nesting dolls White describes in “The Bellini Family,” with “one Russian girl inside another.” We carry within us different possibilities, different lenses and methods of perception which can create the way that a woman’s body creates, preserves, and bears a child. White speaks of her desire for “several bodies to open and put back inside each other, to increase, then decrease when they are overwhelmed.” Creativity, then, is a corollary of the process of creation which also promises reversal, the mind, like a mother’s muscles, snapping taut into place after birth.

Art, however, is not a full, living creation, like a child, as White reveals through her observation of “Seated Dancer, Head in Hands”: “Or if I kneel down on the sidewalk and put my hand inside the imprint of a hand, I am not nearer to touching anyone. As in to touch is to find.” Instead of creating an actual being, art creates the possibility of being. Art forces us, through viewing, to occupy the same space, time, and perspective of both the person depicted and the depicter, as a hand fits into the empty space inside a glove. In viewing, the viewer does not become an other, but is forced to see and be like another, standing “inside the shape of a person.” Still, as White reminds us in “Absinthe,” it is the viewer’s “choice to see,” and to experience. Representation – and the appreciation of representation – demands a kind of empathy not always found in the subject of a work of art, nor in the viewer for the subject, as “the addict” she presents to us in the poem “is not sympathetic. Is less than the suffering itself. I smoked what I could scrape from the bottom of my purse and so on.” These ideas are borne out in “La Savoisienne,” in which the subject is described as she herself is – “she is equal and her eyes do not care who anymore. She can feel alone even on the street, periodically bumping shoulders and the succession of faces looking forward in the cold” – and as she is interpreted through a lens – “There are at least seven kinds of loneliness.”

In “Frieze of Dancers,” White shifts to the perspective of the creator, and of the viewer of creator, who “could say out loud, I am near her whom I have made, who is waiting for God. Which is not brave enough to make me memorable or shimmer.” Here, White points towards what might be the impulse behind both art and addiction, the fear of our own fated vanish from the world. By looking, we are soothed, and we are allowed to trick ourselves into a belief in permanence and importance through the belief that other things and people exist because we observe them: “It was aspirin to sit and look out the window, to listen to other people, sometimes my uncles, in the front room, talking.” But there are limits, and any power we have is not real power, real creation. The speaker realizes that “it is too late to predict the season or the kind of reversal that would change my life. […] I can no longer say anything simply.” Still, to watch and to create provides some kind of comfort, as “I recognize is the reversal of I disappear.” Through creation and observation, we fulfill the desire for “life stilled inside a frame,” and we fight against loss as we do with memory, which, in “Dancers in Blue,” is “movement unhinged.”

With “Portrait of Mlle. Helene Rouart,” White continues her reflection on art, and a viewer’s perception altered by art, as part of the essential human need for comfort, as both follow the “common” desire “to rearrange the body into a comfortable position.” The most base and basic of human urges and responses can be linked to perception, and to proving our existence through being seen by others, even if it means to cruelly force others to recognize us in acts as vicious as rape, which, in “Interior or The Rape,” is a desire “to be seen in the lamp light as a ghost wishes to be seen once and consequently forever,” even in nightmare. This desperate fear of being forgotten pervades the most drastic and the most simple of human experiences, from death to the circle a pony tail holder leaves in one’s hair. It is this fear which pushes us to create narratives, as “all stories persist to explain the end.” We wish not only to persist but also to be understood, which is a task that narrative performs for us. Narrative fights against the absence of structure, the fact that “without a door, it is not your house. Without a house, the children are not sane.” We are kept sane, human, and separate from animals only by manmade structures, buildings and self-built narratives intended to construct others in ways we can understand, so that we can, in some way, gain possession over them, “because, in the big picture, we own nothing.” Sadness, which is “the act of keeping and never what is kept,” and art are responses to this; one draws the baby’s head to preserve “the uneven waves of hair in pencil.” Art, and perception, allows us an escape through seeing ourselves as an other, as the older woman who focuses on the rose tucked as ornament behind a dancer’s ear, “although she would never confess, orange or white, she is much too old, she would like to wear a flower in her hair.” Part of the beauty of art, White suggests, is its ability not only to transport us from ourselves but also to return us to ourselves, reminding us that “we are who we are,” and cannot change that, as “it is useless to be someone else.”

The challenge is to hold on, like the subject in “Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando,” who is drawn upwards by a rope between her teeth, “her gift … to stay attached (if she speaks she will fall), to cleave in her mouth what is pulling away.” Our attachment and attention to others, who reflect us and by their very perceptions prove that we exist, takes away our anxiety, which “does not solve anything.” “If you cannot see your reflection, one book said, you don’t exist,” and therefore both viewer and viewed, artist and subject, strive to capture themselves and others as still images, flash-frozen moments meant to prove their own existence. Absence, however, does have its place, as it is in distance from another we recognize them more fully because we fear their loss, their nonexistence, like “the photographer” who “is afraid when he wakes up from the ‘losing Susanna’ nightmare. Blind, he feels the flat surface of the picture again and again, but he cannot see her image.” Language, poetry, and art are therefore only gestures “towards what is forbidden to say. I am loneliest with other people and require their absence in order to love them.”

God is present in images, then, but more present in motion, in moving away, as God is the creator and controller of time; “God is movement and several women run alongside a train blowing kisses that break against the windows – I press my hands against the glass to feel the sudden pop of disappearance.” Eternity promises an end to movement and therefore to disappearance. Paradise, like art, is a stilled moment, and “hell means to begin again,” an eternal and continual existence in time, in beginning and beginning again. Existing outside of time, the dead in heaven feel joy, the pleasure of permanence; “the dead will approach, in slow motion and dressed for Christmas, when I die.” Heaven, therefore, is a kind of permanence, which leads to a new recognition of the self as something solid, no longer a spot which blurs into and out of existence. This permanent stillness impossible on earth, where “seventy-five pictures of a mouse, hand-drawn, make up less than five seconds of a cartoon,” and “sometimes, at the park, I hear people calling my name, but there are so many people with my name.” The speaker admits to fearing God, who made her but who will also judge the “her” she has made: “whoever I am, creation is over. . . .But what shape or comfort can I make with my mind? The horse holds up her cardboard sign, All words can do now is say.”

Still, the promise of salvation, which is stillness, pushes beyond all such fears with its promises of peace and of a new kind of being which is and remains, rather than swirling continuously with time, into difference, and therefore into change: “And when she is gone, only the backs of their heads who stand and applaud into the absence of movement. Nothing else will happen.” This is God’s greatest blessing, which the artist attempts to replicate over and over, stilling the subject into salvation and offering the viewer a glimpse into the heaven in which they may forever be still, and therefore forever remain, themselves.