|

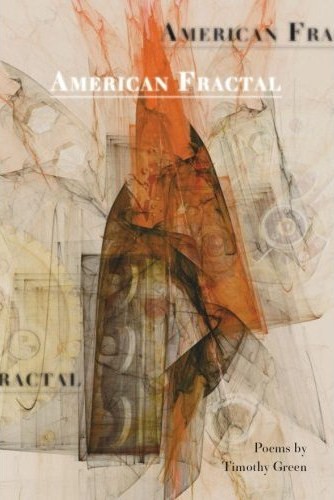

American Fractal by Timothy Green

Reviewed by Karen J. Weyant American Fractal Red Hen Press Perfect Binding, 104 pages ISBN-13: 9781597091305 Link to Purchase

|

|

One could waste a lot of time – precious time – wondering about the title of Timothy Green’s debut collection of poetry, American Fractal. Since math is not my strong subject, I had a friend explain the term fractal to me: it is a shape with a pattern that repeats itself at a smaller and smaller level. Since I thrive on specific examples, she also explained that an unfurling fern is an illustration of a fractal found in nature. Thus, with this picture in mind, I imagined a forest floor – moss, broken branches, tree limbs, and mushrooms – a general chaotic world with order found in the pattern of ferns that were nestled between the other inhabitants. I then entered the pages of American Fractal expecting to find similar patterns unfolding. And I did – except that Green’s forest floor is the world, and the speakers, with their struggle to find their own ferns, discover instead, their answers to the questions our world seems to ponder.

Readers entering Green’s book should not expect to find a straight narrative. Instead, his collection is a smattering of poetic forms and themes. We see speakers wrestle with their place in nature, their role in their own families, their struggles with love and relationship. Often, the characteristic his works have in common is the speaker’s sureness. For example, in “Hip” we learn the story of the speaker’s father whose nickname was “not for how cool he was/in the sixties, nor his sense of style.” Instead, the real story reveals he was “hit by a car walking to school, a whole/year in plaster only his sister would sign”. This father, apparently, spent time recovering and “dreaming up other lives,” an act that the speaker finds sympathetic:

I don’t blame him. Four walls around

a solitude and with the curtains drawn

it isn’t real. And so I draw my curtains.

So, too, I shut the light and leave –

not fitting in any room like my father

never fit, shoulders stiff, a janitor’s

loop of keys already digging at my hip.

My personal favorite, “Hiking Alone” is more contemplative, where the poet finds comfort in nature, even though this solace may be “sore arms and a sunburn.” In this work, the poet muses “How easy it is to paint epiphany, I think, like/the gaudy sunset now settling above the tree” and “How easy, too, it would be to slip off this ledge/to get lost here, fall asleep on this rock and//let the cold night wake me.” Certainly, the pilgrimage detailed in this poem is a lonely one, but not sad, for he ends up sure of one thing:

Come morning I’d find the dirt road

and then my car at the end of it. Brush the dust

off my pants. Buckle myself back into habit

with a metal click like the sound of my one hand

clapping for joy – however briefly – at all we

ever wanted: a little darkness to climb out of.

Nature once again takes center stage in “A Tourist’s Guide Through Big Sky Country” which is a roadtrip detailed in couplets. Reading through this verse, one can imagine a driver or passenger giving specific directions: “See the bare sky, not another soul for miles/as proof you’re not alone.” Other pieces of advice also sound sure: “See for yourself how easy it is on the prairie/to believe in God, in the perfection//of the human form.”

Other poems in Green’s collection are less lyrical, less dreamy, and more assertive. In “The Urge to Break Things” the poet discusses anger explaining, “It comes on young and fast, first with toy trucks, then with//lead pencils snapped in half.” His work, “Saddled” is a love poem – of sorts. Forget the stereotypical greeting card declarations of emotion. Instead, we see the speaker explain that “Love is a horse sound the throat makes when//it’s sore. I gurgle, I gag on a horse pill. But love/is an easy thing to swallow.”

So the final question may be, do we as readers see the unfurling fern in the forest floor of Green’s collection? The answer is yes – sometimes. Yes, Green’s poems provide the unflinching beauty in order. And yes, Green examines the questions that poems are supposed to ask – inquiries about identity, loss and love. But even more certain is the fact that Green does more than find order in the world’s confusion. He is also a poet who relishes in the act of exploring this confusion, of finding the answers.